Yesterday was an East End Cemetery day for us, as are most Saturdays that we’re at home, in Richmond. By the time we arrived—we were on the late side—the site was humming with activity. Regular volunteer and Friend of East End Mark had briefed a crew on the cemetery’s history and best practices for clearing plots. Members of the group had grabbed tools and were already migrating toward a semi-cleared section to pick up where a team had left off last Sunday. Melissa, another core volunteer and Friend, was a few yards away talking to a multigenerational group with a dynamic and composition—from little squirts to seniors—that telegraphed family.

None of us had seen the Jones at East End before. They had come to tend the family plot for the first time in years after hearing that much of the place had been reclaimed from nature by volunteers. Fred Jones, the oldest member of the cleanup squad, told me that he had come out many years ago with his father, Alexander, to tend the plot before he was laid to rest there alongside his wife, Cora Belle Mebane. Most times his dad soloed, he said—he was happy doing the weed pulling and brush removal himself, and he did it until he was 90 years old. The family tried to keep up the work after Alexander passed in 1994, but they couldn’t beat back the vegetation that grew in the dozens of untended plots around theirs. Family member Debra Cain chose this day, March 31, to reunite the family at East End and to revive the tradition her grandfather had started. They came more than a dozen strong. With rakes, leaf blowers, and hands, they gathered bucket after bucket of flora from the Jones plot, plus those abutting it and several beyond.

Why does a single meeting on a single day with this family matter? To us, it represents a handful of small victories. It is a direct and living link—13 links to be exact—to a place we have cared for and the people buried there, whose histories we are trying to reclaim. It is the kind of recognition that matters most—smiling, talking, connecting with descendants for whom this ground is sacred and vital, as it is to us.

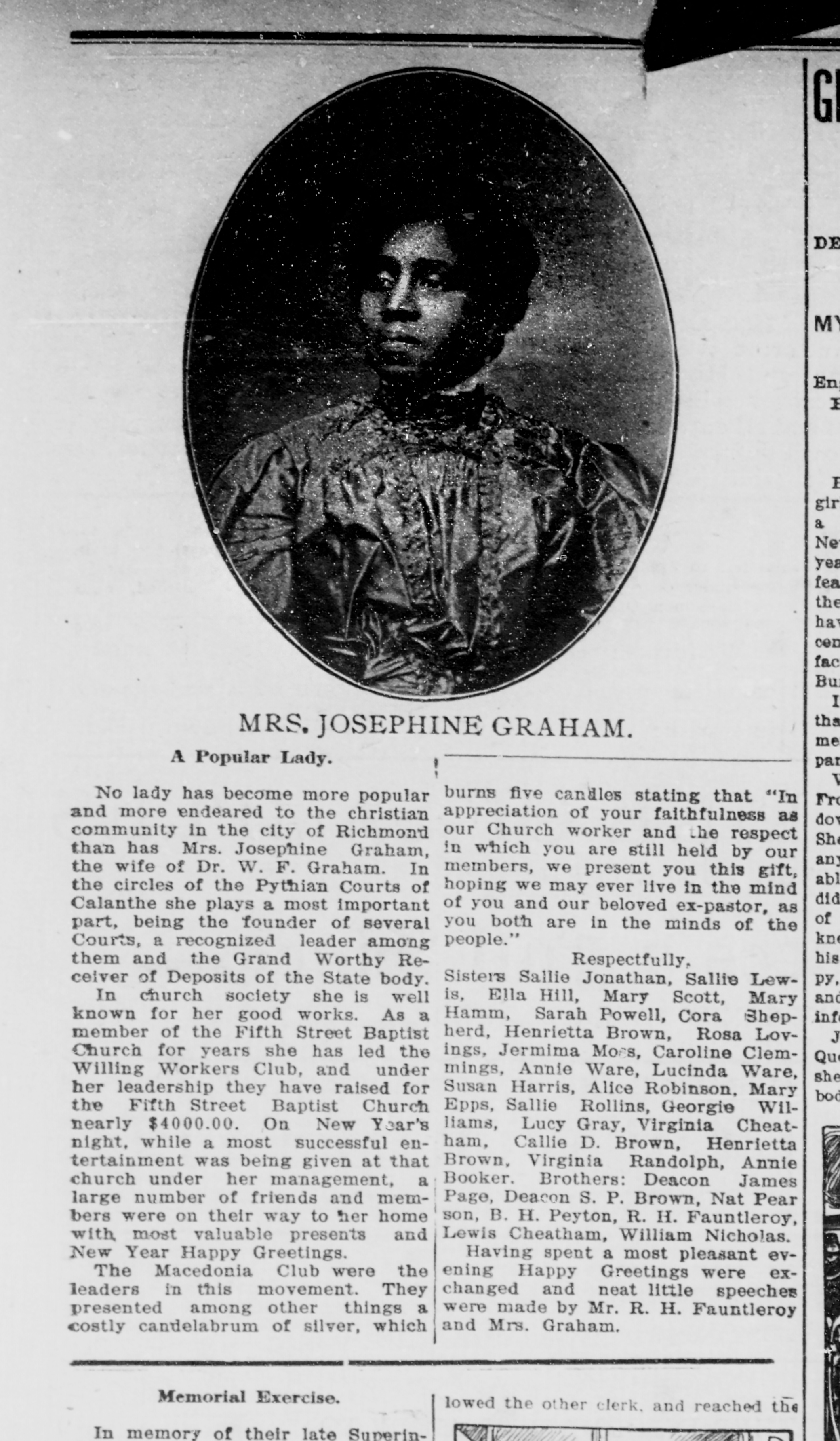

Along with other Friends of East End, Erin and I have been at this work, peeling back decades of overgrowth from a historic black cemetery, for more than three years. We came to East End originally, in 2014, to shoot video. As we were gathering stories about and images of Magruder and my great-grandparents, Mat and Julia Palmer, through archival research and interviewing, we wanted to show people revealing African American history, literally, with their hands. This was happening, stone by stone, at East End.

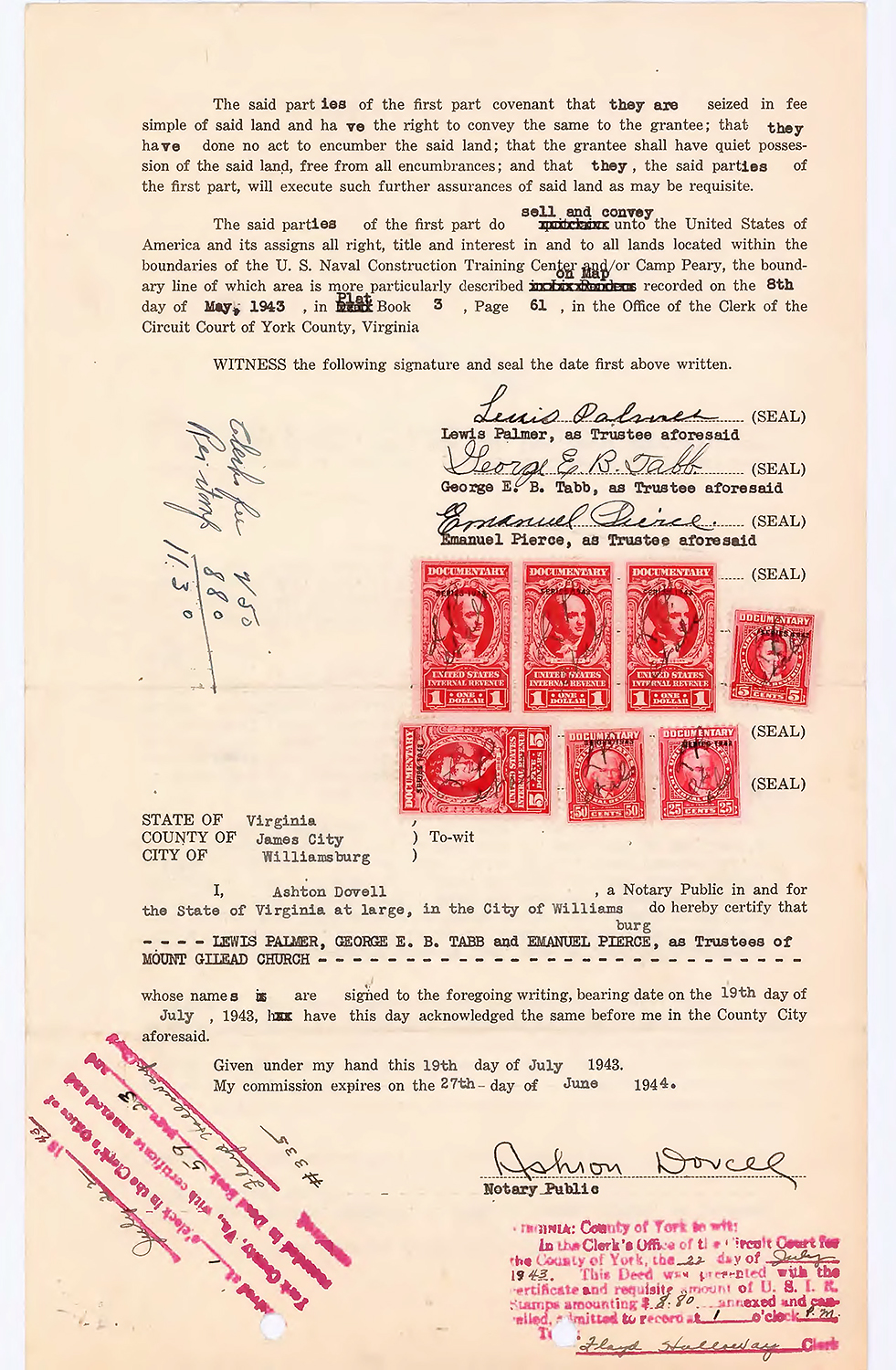

East End quickly became much more than a visual proxy for Old Orchard, the cemetery on Camp Peary where we were no longer allowed to shoot for the documentary. We learned that to make the ground talk at East End—first, to pull long-buried grave markers from tangles of vines and inches of soil; and second, to glean information from databases about the people memorialized on these stones—was to make the ground talk for all of Virginia’s displaced, disregarded, disenfranchised, and dispossessed black communities. Not that their stories are interchangeable. We have found no significant connections between East End and Old Orchard families (yet), but we have learned through our research into 19th- and early-20th-century Richmond and Magruder that the histories dovetail. The afterlife of Jim Crow, as Erin terms it, is as evident at East End as it was to us at Old Orchard—and in the lives of those at rest in both places. Moreover, the stories we uncover at East End, such as that of William I. Johnson—who, like Mat, was enslaved in Goochland County and freed himself to fight in the Civil War—augment and complement what we learn about Old Orchard. It is with this knowledge, both specific and contextual, that we return to the Magruder story. —BP