OLD ORCHARD CEMETERY AT CAMP PEARY, VIRGINIA

U.S. Congressman Bobby Scott has offered to communicate with the Department of Defense on our behalf about the terrible state of Old Orchard Cemetery, the black burial ground on Camp Peary at the heart of our documentary. Old Orchard is the last tangible remnant of the black community of Magruder (where my father and his parents were born) that was uprooted in 1942 to build the base.

We are thrilled by this news—and we understand that there is no guarantee anything will come of it. Camp Peary is a top-secret training facility; its records—and officials—are largely beyond the reach of most citizens. But this could be a simple matter, of both maintenance and justice. York River Presbyterian, Magruder's white church, and its cemetery, also on Camp Peary, have been beautifully preserved and maintained for more than 70 years. Such treatment honors those who worshipped at the church before the government took the land, and it honors the people interred at the cemetery, including the Unknown Confederate Soldier. Committing to perpetual care of Old Orchard would honor the once-enslaved people and their descendants buried there, including those in my family, whose own church was torn down by base commanders not long after I was born.

EAST END CEMETERY, HENRICO COUNTY AND RICHMOND, VIRGINIA

As he promised this morning, Gary Martel, the executive adviser to the head of Virginia’s Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, passed on my request for an interview to a senior law-enforcement officer in his agency. An hour or so ago, a DGIF conservation police captain, manager for Henrico County and Richmond, called me and promised to look into the incident. "Send me what you have and I'll follow up on it personally," he told me. He gave me his cell phone number.

I’m asking DGIF, a state agency, to investigate the situation as a public-safety matter, because Henrico Police Division will not—and because the hunters may have roamed beyond HPD’s jurisdiction into Richmond.

Fundamentally, the danger that someone might get shot while looking for a relative’s gravesite or scanning the trees for songbirds is real. The next hunting season isn’t far off. And those “seasons” may not even matter. As a different conservation police officer told me over the phone, this group of hunters was most likely trespassing on someone’s property. “I doubt they would have had permission to be there hunting.”

The half dozen or so hunters we witnessed—and heard—on December 13, 2014, roamed across various plots of land with their firearms. If you don't have permission from the owner of the property, you cannot cross that person's land with your gun. The hunters did not have permission to enter at least two of the properties we believe they crossed—I have interviewed the owners, who deny granting permission to any hunters.

“Where did the men discharge their weapons?" I asked in an email to the sergeant who supervises the two responding Henrico Police Division officers.

His reply: “The officers that responded state, that during the entire timeframe that they were on scene, no weapons were discharged, providing them with no personal observation of this occurring. During our conversations you have stated that you heard the shots being fired, but could not provide an exact location of where they came from.” [My emphasis added.] Listen for the boom on the video below at two minutes and 23 seconds. I did not add this gun blast. The officers were there.

I emailed a link to the HPD officers, the supervising sergeant, and their superiors.

This is the sergeant’s reply in full:

“Thank you for your reply. As discussed previously, this investigation has been closed. It has been noted that you possess video of the day in question and if there is ever a time that it is needed, you will be contacted. From this point forward any and all questions in regards to this property or surrounding properties will need to be presented by the property owners themselves. No further information will be presented to anyone without legal standing to the property to protect the owners rights. It is respectfully requested that any email correspondence to the Henrico Police Officer's government email addresses that you have been using regarding this matter, is immediately discontinued and to remain discontinued unless permission is granted in the future by a specific officer. Thank you sir.”

It appears to me that in this case the right of hunters to roam across property lines and shoot stuff unmolested trumps the rights of me and other citizens to visit cemeteries, even private ones, that are open to the public without getting shot.

Although HPD told me an investigation had been conducted, it does not appear to have been an especially thorough one. HPD closed its investigation before speaking to the original complainant, the scoutmaster who called about the hunters, fearing for the safety of his Boy Scouts stuffed in the back of a van. I spoke to the scoutmaster a month after the incident, after HPD had closed its investigation, and he assured me that no official from HPD or Henrico County had spoken to him after that day.

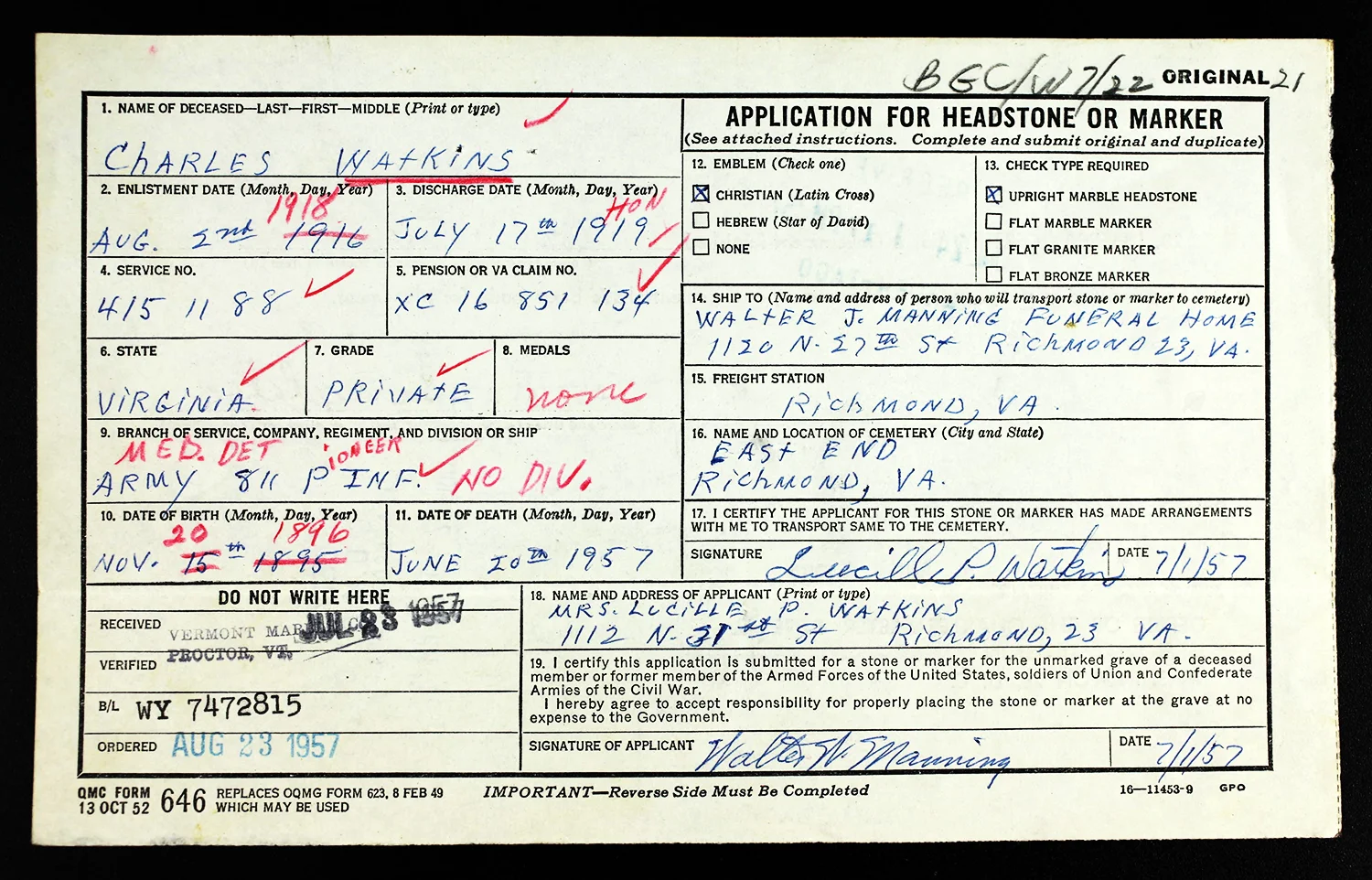

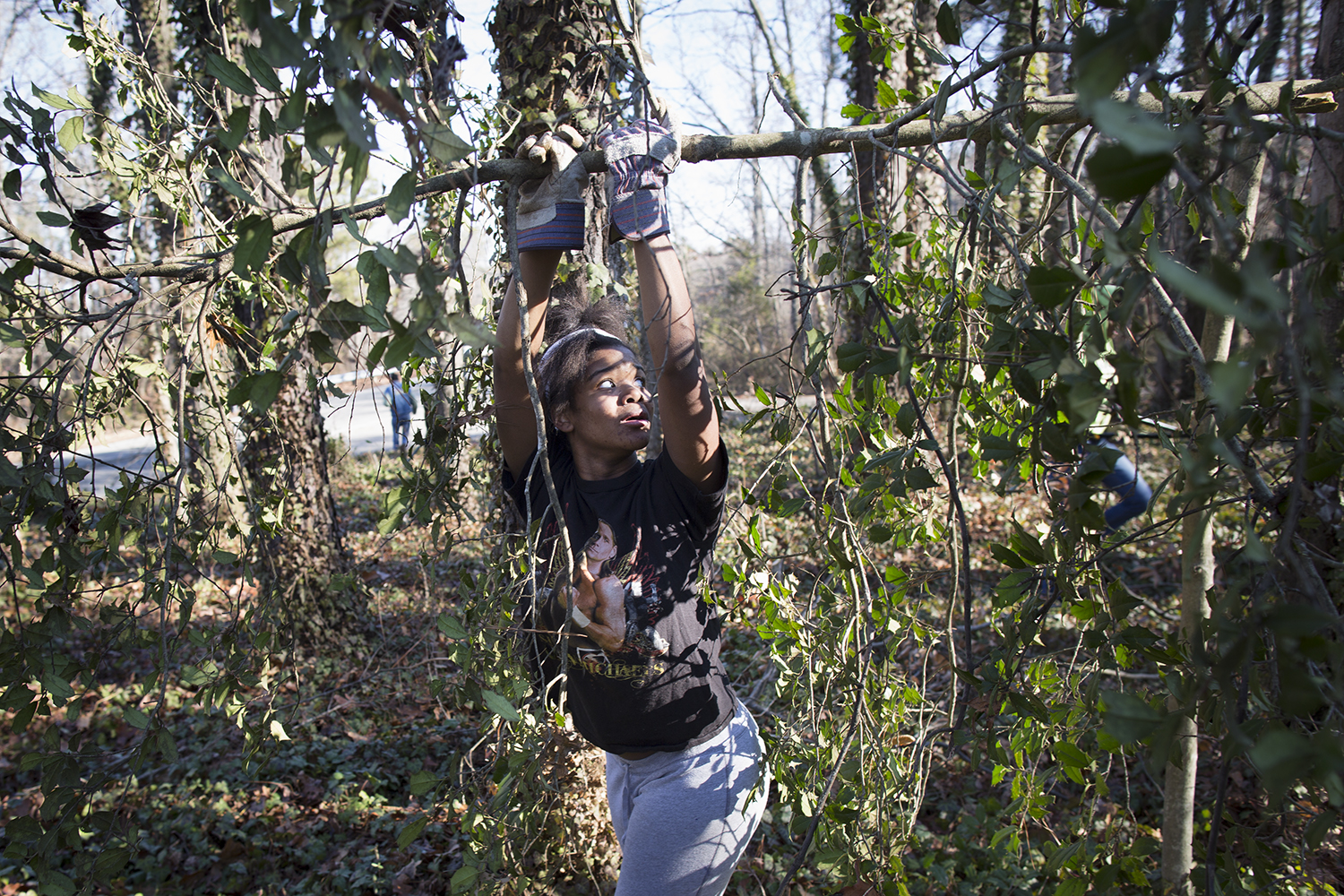

I’m not cemetery obsessed, though it may appear that way from the huge volume of stories and pictures I’m producing in and about such places. Erin and I wind up in burial grounds so often because our search for hidden African American history leads us there. So little was recorded in books, and so much land was taken, that cemeteries, as ramshackle and neglected as they may be, are among the few physical traces of black communities such as Magruder, Oak Tree, and Bigler Mill, in York County, Virginia. And here in Richmond, with the decimation of once-vibrant black communities such as Jackson Ward, East End and Evergreen cemeteries connect us directly to the people, such as bank founder Maggie Lena Walker and Richmond Planet editor John Mitchell, who made black Richmond great so many generations ago.

We go where the history is, and where our ancestors are, just as so many others do—or would do, if they were allowed (Camp Peary), or if they didn't have to worry about getting peppered with buckshot.

We spend a lot of time among the living, too, and we'll write more about them soon. —BP