EAST END

Just shy of a dozen volunteers appeared on Sunday for the work day at East End—six college students and five regulars.

The students, women from the University of Richmond’s Alpha Phi Omega, raked, wrenched, and lopped branches in a plot where a Martin Luther King Jr. Day cleanup team had worked. Two of the women, exchange students from Shanghai, spoke to each other softly in Mandarin as they worked together clearing a particular tangle of thorny, creeping vines. Volunteer coordinator John Shuck, who maintains the East End Cemetery blog, estimates that he and the volunteers have unearthed and recorded about 800 graves and that they have cleared about 15% of the cemetery itself in roughly a year.

I shot still photos and video for the first two hours, and pitched in for the last three. Erin settled into the dirt immediately. From beneath glove-puncturing, hand-lacerating vines, she unearthed headstones and a couple of aluminum grave markers that look like license plates but are smaller—she has some sort of stone-detecting radar in her fingers and in the soles of her feet.

Erin found a huge stone for Glenn Nelson Jones and also a temporary marker for June Anderson, who died Sept. 9, 1967. And others.

Shuck keeps track of the names, and he photographs every marker and headstone. Objects—the Virgin Mary near the Anderson sign, and the sign itself—he leaves in place. Such things lose their historical, genealogical, or archaeological value when removed from the plot they mark and the people they represent.

In my wanderings, I tripped over a hard lump that hid under a bonnet of English ivy. Charles Watkins’s service in the army earned him a Veteran’s Administration headstone. There are no tender epitaphs on VA stones, only data, which is especially valuable to anyone trying to find the person being memorialized.

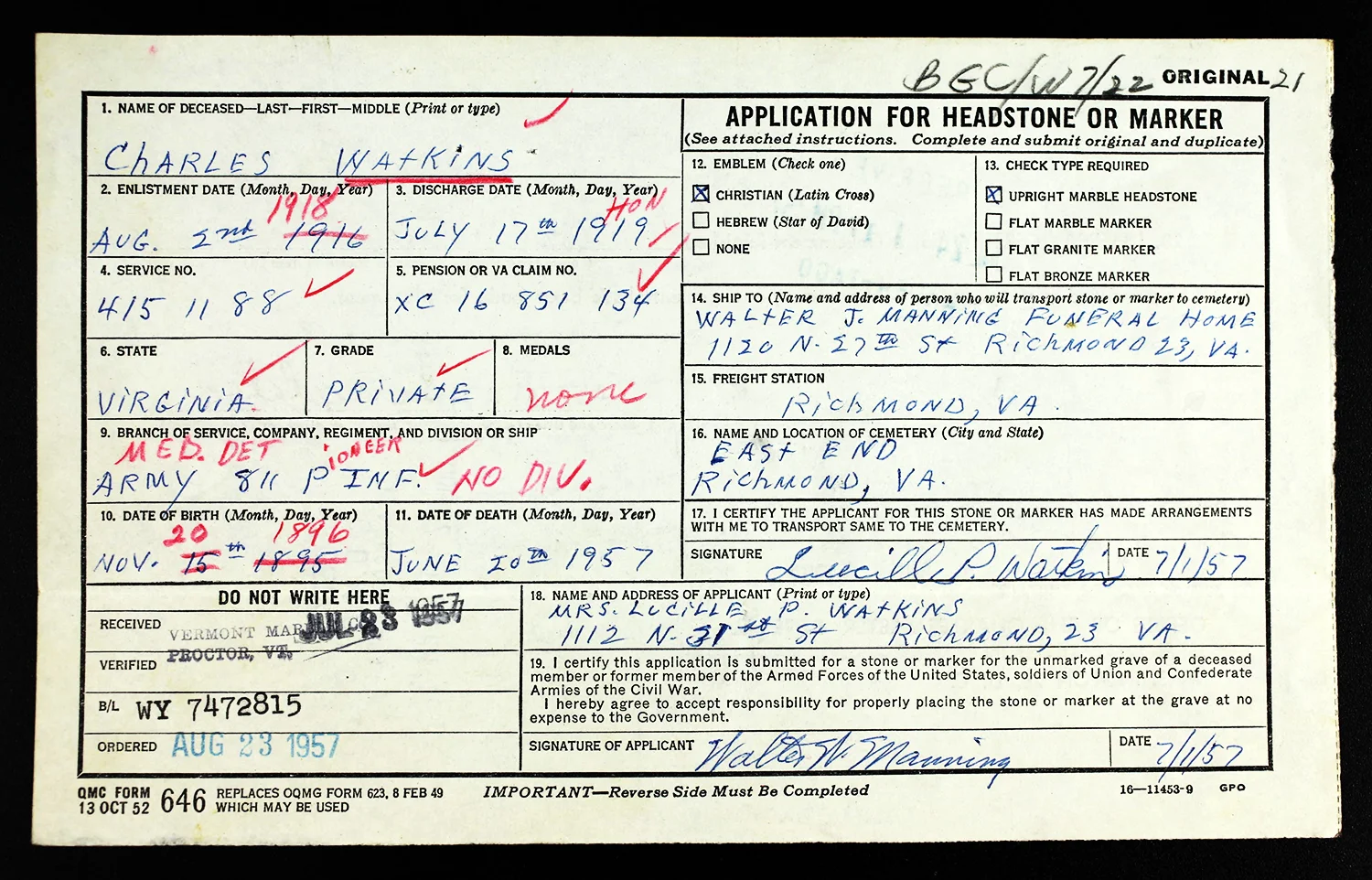

I plug his date of birth and place of death (I assume “Richmond”) into Ancestry.com, and up comes a perfect scan of QMC Form 646, Application for Headstone or Marker, signed by his widow, Mrs. Lucille P. Watkins, in July 1957.

I enter into Ancestry the information gleaned from Form 646—notably his correct birth date, November 20, 1896, red-penciled over the incorrect date—and his draft cards for World War I and World War II appear. Watkins was born in Appomattox County, Virginia, and was an unmarried, 21-year-old wagon driver when he first registered for the draft. In 1942, when he registered again, Watkins was 45. He was five feet, six inches tall and weighed 154 pounds. Both cards list his race as “Negro.” More search-engine scouring calls up the 1920 US Federal Census with a “Charles Watkins” of the right age, in the right city . . . I have only scratched the surface, literally at East End and figuratively at my desk, but I’m still astounded that I have learned all of this.

OAKWOOD

You barely burn any gas driving from East End to Oakwood Cemetery—it's just two or three turns, then a hard right off East Richmond Road through a narrow gate puts you in the Confederate section. (A hard left puts you in the heart of an African American neighborhood.)

We visited Oakwood at sunset after finishing our work day. New knee-high Confederate flags were planted next to the cube-shaped stone grave markers. It is a neat and orderly place, and it should be. The land is owned by the City of Richmond and maintained by its Department of Parks, Recreation and Community Facilities–Cemeteries Operations Division.

State law, specifically a provision in the Code of Virginia, authorizes annual payments to “Confederate memorial associations and chapters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy” for routine maintenance of their cemeteries and monuments. The state pays $5 ("or the average actual cost of routine maintenance, whichever is greater") per approved grave. Oakwood has upwards of 17,000 Confederate graves, but the Sons of Confederate Veterans are approved for only 2,294 of these. Still, that's real money.

These same Confederate groups may also apply for money to perform "extraordinary maintenance, renovation, repair or reconstruction of any of their respective Confederate cemeteries and graves and for the graves of Confederate soldiers and sailors." The money comes from the General Assembly. Our taxpayer dollars are at work here, keeping the Confederacy alive in public memory—and buttressing Gone With the Wind–type myths that were created to disguise the true nature of the Southern slavocracy.

But, one must give credit where it is due: Oakwood supporters raise private funds to preserve and upgrade the Confederate section. The Virginia Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans is an IRS-registered nonprofit, a 501 (c) (3), with its national HQ in Columbia, Tennessee. It had more than $8 million in assets in 2013.

Over at East End, most (but not all) of which is in Henrico County, Shuck was figuring out how to pay for the Dumpster we had been emptying bits and hunks of Mother Nature into. It's been on loan from a local business for months—and they've been emptying it, too, for free. Time for others to step up, it seems. —BP